This project is a collaboration between VCU’s Center on Society and Health and the Virginia Department of Health.

Key Findings from Virginia’s 2023 Opioid Cost Data

Lifesaving Care Would Help Every Community, Most of All Poorer Areas

Mayor Danny Avula joins staff from the local non-profit Health Brigade, the Virginia Department of Health and the City of Richmond’s Opioid Response team in unveiling a new vending machine with free harm reduction supplies on July 30, 2025. Lifesaving projects such as this one have helped the City increase access to naloxone, fentanyl test strips, and hygiene items to support community members wherever they are on their journey. (Photo: The City of Richmond’s Office of Opioid and Substance Use Response.)

Fatal drug overdoses have been Virginia’s leading cause of unnatural death since 2013. Opioids, and specifically fentanyl, have driven most of these deaths. After many years, though, we have finally seen a glimmer of hope: the rate of fatal drug overdoses fell nationwide in 2024 by an average of 27%.1 Virginia’s rate dropped by 43% – although racial disparities persisted, even across the improving numbers.2 Additionally, it is important to note that many people who would have been at risk may have perished already – a very sad possibility.3

On the whole, these trends are encouraging: fewer lives are being lost to overdose.

What the numbers don’t capture: the crisis’ ripple effects across our communities. As of 2023, nearly one in three Americans knew someone who has fatally overdosed,4 most often a close family member or friend – a devastating emotional reality. Compounding the intense grief, loved ones and the communities around them also typically face immense financial stress as a result. To better understand what this crisis has felt like for Virginians, we explore the latest available opioid-related economic data, from 2023. Economic data can show how the epidemic has impacted our individual and shared financial resources.

Of course, we can’t monetize or measure every benefit of helping people stay safe and live well. But our data show that better opioid outcomes would improve community life and boost every single community’s financial health. These insights on our recent past can also help us strategize for a better future.

Here are 12 takeaways from the latest available data.

Most Lives Lost Could Have Been Saved

In 2023, we lost 2,082 people to opioid overdose in Virginia. Each person’s life experience and relationship to their community was unique. As public health researchers, we seek to honor their memory by understanding the context they shared: a system of care unable to offer the help they needed.

How do we know that our system of care failed them? CDC data show that 70% of drug-related deaths in Virginia were preventable in 2023, and most involved opioids.5

With evidence-based opioid care, we know we can improve outcomes. In fact, even more overdoses (2,235) were reversed than the total number of fatal overdoses – thanks to comprehensive harm reduction efforts, such as the services offered by the Richmond-based Health Brigade.6 That means for every life lost, at least one other life was saved.

Anyone can use substances, including opioids, in ways that harm their health. If we can stay alive, though, we can potentially reduce harmful substance use and recover. Evidence-based opioid care can keep us alive. Research-based approaches to care can:

- prevent harmful substance use,

- reduce harm among people in active use

- help them find treatment,

- and potentially recover

Unfortunately, not everyone has the same access to the resources they need to survive unhealthy substance use. Where we live and who we are can make a difference in how likely we are to survive.

Better Outcomes Would Have Boosted Every Single Local Economy

Without exception, every community faced opioid-related costs – and would have benefited economically from better opioid outcomes.

- Virginia’s total cost amounted to $5.2 billion.

- Each Virginian would save an average of $593 with better opioid outcomes, if we spread the total cost across Virginia’s population (including all people – not only those directly affected by opioid use).

We detail how families, businesses, and taxpayers could have benefited from better outcomes.

Where You Live Matters

Our detailed map is the first of its kind for Virginia: it shows the economic losses each city and county incurred in a single year due to the opioid crisis. These data offer only a narrow snapshot of the epidemic’s immense harm. At the same time, mapping the economic ripple effects can help us pinpoint where investments in opioid care may be most urgently needed.

Annual costs varied across localities due to differences in:

- population size

- opioid overdose fatalities

- rates of unhealthy opioid use (UOU)

With better opioid outcomes, every city and county in Virginia would have saved money. Across our data, several patterns emerged:

- Even small, rural communities with low rates of opioid use and no fatal overdoses would have benefited – due to the crisis’ ripple effects across every sector.

- Places with higher rates of UOU and opioid fatalities included a mix of metro and rural areas. These places faced higher per-person costs, because the epidemic’s effects were spread across fewer people. The City of Hopewell topped the list at $2,344 per person, trailed only by per-person costs in the following places: Richmond ($2,284), Petersburg ($2,084), the City of Norton ($1,917), and Portsmouth ($1,754).

- Metro areas faced higher total costs, due to higher counts of people with UOU and opioid fatalities. The City of Richmond topped the list at $526 million, followed by Fairfax County ($318 million), Virginia Beach ($280 million), the City of Norfolk ($275 million), and Henrico County ($263 million).

A Feeling of Alienation Is Likely Connected to Widespread Opioid Use

As our data show, unhealthy opioid use – without evidence-based care – can result in not only immense grief, but also staggering economic hardship. Sadly, communities where people are most at risk for fatal overdose – and its economic consequences – are also already places where people are likelier to experience mental health conditions.

When people feel disconnected from the culture around them, they may also lack a sense of their life’s meaning – a feeling that can be more or less likely for us depending on who we are and where we live. Addiction experts including Dr. Carl Erik Fisher believe this sense of “social wounding,” or alienation from society, drives widespread substance use. In his book The Urge: Our History of Addiction (Fisher, 2022, p.39),7 he explains how in communities where many people are emotionally hurting, large numbers of them may turn to substances to soothe painful feelings. This framework helps us in:

- exploring how opioid use is experienced, distributed, and managed across a population

- understanding that some communities face higher risks than others

Feeling alienated can place people at higher risk of mental health conditions. Our colleague Jacqueline Britz and her team found that untreated mental health disorders are a major risk factor for fatal opioid overdose.

They explain, “Communities with missed opportunities for early opioid use disorder (OUD) diagnosis also have missed mental health diagnoses related to overall less interaction with the healthcare system, which can compound the risk for opioid mortality.”8 Making the situation worse, inequities in mental health care appear to be driving racial disparities in Virginia’s opioid outcomes.

Understanding where investment is needed matters because Virginians currently face differences in opioid-related health and economic outcomes that are both unfair and avoidable. As Dr. Fisher (2022, p. 299)7 writes, “Not only are the factors driving addiction distributed inequitably, but access to recovery is also inequitable. Poverty, class, racism, sex-based discrimination, and other drivers of inequality powerfully affect people’s ability to enter into and sustain recovery.”

One silver lining: we can address the current inequities our communities are experiencing, including through connecting them to mental health and substance use care early on. Furthermore, we can intentionally focus our efforts on where people may most need support. As Britz and her team explain, “The use of comprehensive socioecologic data to identify the precursors to fatal overdoses [...] could allow earlier intervention and reallocation of resources in high-risk communities.”8

Places with the Highest Overdose Rates Were Already Poorer

Communities vary widely in their access to resources that can help them achieve better substance use outcomes, a concept known as recovery capital.9 In areas with higher poverty and lower income, people have less access to resources that support better opioid outcomes. Put simply, not having enough money can make it harder for people to survive substance use and live well (whether they are using substances or not).

In the places where people are likeliest to fatally overdose, communities also face among the highest opioid-related costs per person. In other words:

- Communities with high overdose rates already face immense collective grief.

- They face even greater economic hardship in annual cost per person as a result, compounding the emotional pain of losing loved ones to overdose.

Our data showed:

- Places with the highest opioid costs per person were also already poorer, with lower median household incomes than Virginia as a whole. These included: Hopewell, Richmond, Petersburg, Norton, and Portsmouth.

- The highest labor losses per person were all found in places with high poverty rates. These included: Hopewell, Petersburg, Richmond, Norton, and Roanoke.

Localities with Highest Annual Opioid Costs, 2023

| Locality | Income | PovertyRate | Local All-SectorOpioid Costs* | Local Lost LaborOpioid Costs* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hopewell City | $44.2K | 24.0% | $2.34K | $1.71K |

| Richmond City | $54.8K | 19.8% | $2.28K | $1.61K |

| Petersburg City | $44.9K | 21.3% | $2.03K | $1.44K |

| Norton City | $35.6K | 28.3% | $1.92K | $1.38K |

| Portsmouth City | $54.0K | 17.2% | $1.75K | $1.13K |

* Costs Per Person

Hard-Hit Areas Had High Percentages of Black Residents

Black Virginians are already more than twice as likely as White Virginians to be living in poverty.10 Our data reveal that Black Virginians were also overrepresented in the places with the highest opioid costs, both per person and total.

Since 2019, fatal opioid overdoses in Virginia have shifted from rural White areas to urban Black communities – and intensifying with the COVID-19 pandemic. By 2023, non-Hispanic Black Virginians (subsequently referred to as Black) were dying from opioid overdose at nearly twice the rate of non-Hispanic White (subsequently referred to as White) Virginians. In addition to the human cost, our data show these racial disparities’ economic consequences have significantly harmed Black urban communities, especially in central Virginia.

- The percentage of Black residents was two to four times higher than the state average (18.5%) in four of the top five localities with the highest all-sector costs per person: Hopewell (41.2%), Petersburg (74.6%), Portsmouth (51.2%), and Richmond (41.6%).

- An above-average percentage of Black residents lived in nine of the top 10 places with the highest all-sector total costs, predominantly in the metro Richmond area and Hampton Roads.

All of the top five localities with the highest health care costs per person had at least double the state’s average percentage of Black residents: Hopewell (41.2%), Petersburg (74.6%), Portsmouth (51.2%), Richmond (41.6%), and Sussex County (54.7%).

Black Virginians are 1.9 times as likely to die from an opioid overdose than White Virginians and 2.7 times as likely to die as Hispanic Virginians.

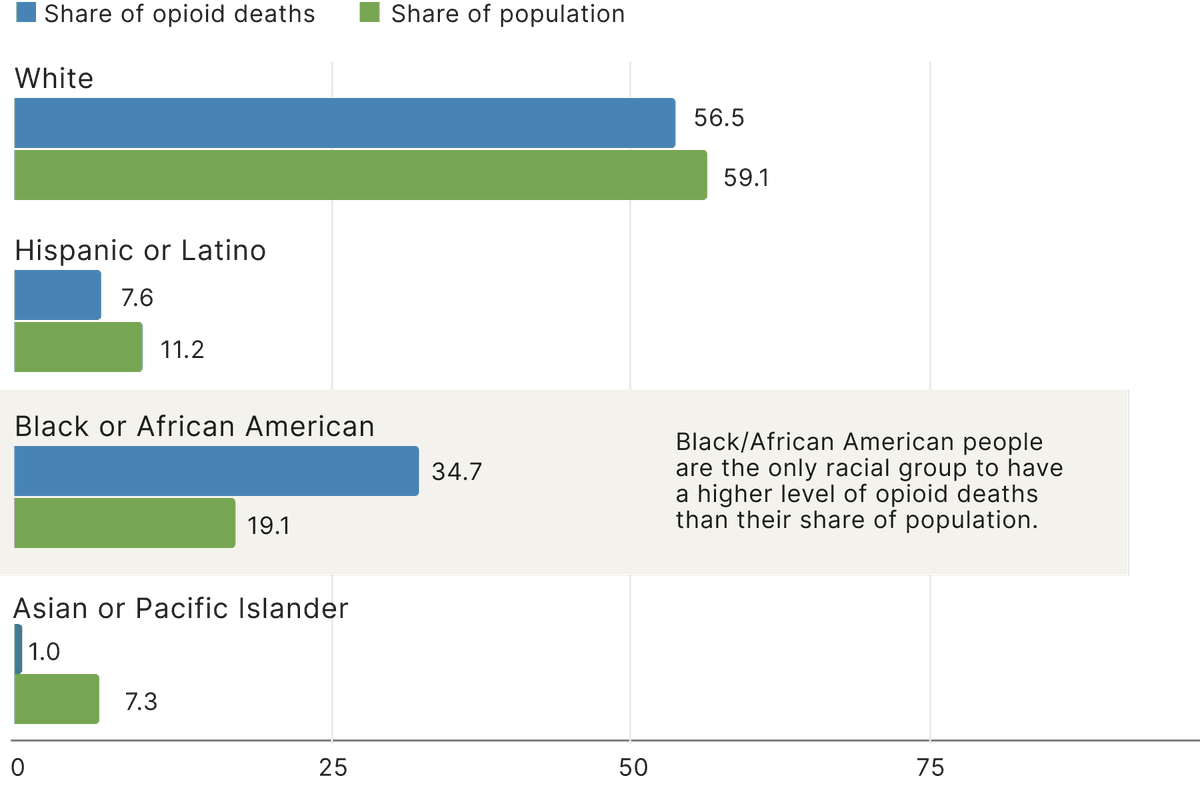

Share of Opioid Overdose Deaths and Share of Population, by Race and Ethnicity, 2023

* American Indian/Alaska Native people also experienced fatal opioid overdoses, but their deaths represented less than 1% of Virginia's total.

Rising Fatal Overdose Rates Among Hispanic Virginians Also Meant More Economic Hardship

The opioid crisis’ total economic costs have also hurt Hispanic residents in recent years, primarily in Northern Virginia. Like non-Hispanic Black communities:

- Hispanic Virginians are already nearly twice as likely as non-Hispanic White Virginians to live in poverty.10

- They have faced “structural inequities and disparities in treatment access,” including access to buprenorphine, a key medication-based opioid treatment.3

- Hispanic communities’ overdose death rates (largely driven by opioids) increased more quickly than White communities’ between 2019 and 2022.3

In Virginia, opioid overdose deaths tripled between 2019 and 2023 in Hispanic communities.2 Hispanic people’s fatal opioid overdose rates were lower than Virginia’s average in 2023. Even so, they make up a significant percentage of the communities most economically impacted, with a higher percentage of Hispanic residents than the state average (10.7%) in:

- Fairfax County (17.4% Hispanic), with the second-highest total all-sector opioid costs

- Prince William County (25.7% Hispanic), the seventh-highest total opioid costs

In addition to Black and Hispanic communities, other groups have also been harmed. While there are comparatively smaller communities of Native people in Virginia, they have also been affected by the overdose crisis. Nationally, Indigenous communities faced the highest overdose death rates – double the national average in 2023.11

Families and Businesses Lost Billions in Lifetime Productivity

The people most impacted by the opioid crisis have experienced the immeasurable emotional pain of grief. Our data also show that opioid-affected families and businesses experience the majority of the crisis’ economic harm, paying 53% of the state’s total estimated costs – higher than the federal, state, and local governments combined.

The biggest share of these costs came from lost lifetime earnings, which make up 46% of our total cost estimate. While the majority of people in active use have jobs, many struggle with daily living.12 Evidence suggests they are likelier work in jobs that have both:

- a high risk of occupational injury

- less available paid medical leave and job security13

Some of the jobs that have been most affected by unintentional overdose nationally include construction, extraction (e.g., mining), food preparation and serving, health care practitioners, health care support, and personal care and service.14

Though we can’t monetize or measure every positive impact, better opioid outcomes would help families by saving them $2.3 million in potential earnings alone over a lifetime, by giving them more healthy, working-age years and resulting in fewer opioid-related arrests. While we are missing the following data in our model, better outcomes would also help families by:

- decreasing the financial risks associated with opioid-related imprisonment. Imprisonment can reduce people’s future earnings by 52% – resulting in $500k in lost earnings over a lifetime, impacting their whole families16

- increasing people’s capacity for the unpaid domestic labor of caregiving, cooking, and cleaning in their homes17

- easing the pressure on grandparents and other relatives who may be caring for opioid-affected children who are their kin18

We also know that better opioid outcomes would benefit families and employers alike by:

Hepatitis and Other Blood-Related Infections Drove the Majority of Opioid-Related Care Costs

More than overdoses, health conditions indirectly related to opioid use drove the majority (76%) of opioid-related health care spending. What’s the connection?

- Injecting drugs such as opioids can place people who use them at risk for becoming infected with bloodborne diseases, such as hepatitis B, hepatitis C, HIV, and tuberculosis.

- If a person becomes pregnant while using, their child’s health may be impacted with neonatal abstinence symptoms, as well.

As with other opioid-related health issues, evidence-based care (including harm reduction) can improve outcomes, including by lessening the spread of opioid-related conditions such as hepatitis and HIV.

With better prenatal opioid care for pregnant people, improved care for opioid-exposed newborns, and more care available to all people in active use, we could have saved $817 million in health care spending on opioid-related conditions.

“There is not a sufficient amount of money we could give to these mothers, or these children ... This was a generational plague for our county. This was a scourge.”

Children in Affected Families Need Support

When parents are in active use, they face higher risks of becoming incarcerated, unwell, or dying due to opioid-related causes. Unfortunately, this means they are not always able to safely care for their children without additional support. When opioid-affected parents and children separate, the impacts can be immense:

- Opioid-affected families may experience diminished quality of life21 and often intergenerational trauma as a result of the crisis.22

- In addition, relatives may need to step in to care for children. Kin caregivers may lose wages, face significant caregiving expenses, and need to provide specialized care – all without the financial support given to foster care families.18

Publicly-funded programs around them must also respond. By preventing more parents from becoming incarcerated, unwell, or dying due to opioid-related causes, we could have saved:

- more than $393 million per year on Child Welfare Services, which may place a child in foster care or a different environment if their parents are not able to care for them

- more than $170 million per year on K-12 education, which offer affected children counseling, academic support, and other trauma-informed services

At a national level, many places where kids are most exposed to the opioid crisis also have the least economic resources to respond – potentially limiting the support schools can afford to offer to protect children.23

Due to legal requirements, most of Virginia’s opioid settlement funds must also go directly to reducing harmful opioid use – which means they may not be used for supporting families affected by the crisis. Hard-hit Tazewell County in Southwest Virginia, for example, tried unsuccessfully to use the funds to help foster youth with college scholarships. County Administrator Eric Young commented, “There is not a sufficient amount of money we could give to these mothers, or these children … This was a generational plague for our county. This was a scourge.”24

Criminal Justice Services Represent the Smallest Fraction of Opioid-Related Costs in Our Data Model

Not everyone faces a criminal record as a result of their opioid use. For people who are arrested and incarcerated due to opioids, though, the social and economic impacts are wide-reaching – especially on their families. We estimate that every locality has been affected, with each losing at least some potential productivity to opioid-related incarceration ($91 million total statewide).

The annual economic costs related to law enforcement, courts, and incarceration alone, though, make up less than 4% of our state total, at $129 million.

With that said, the criminal justice system is a key partner in Virginia’s opioid response – from first responders reversing overdoses with naloxone to corrections staff who partner with non-profit recovery organizations and those who help individuals to navigate reentry into society.

Some Virginia jail systems have received national attention for their evidence-based opioid response programs. Chesterfield County, for instance, integrates medication for opioid use disorder with trauma-informed services such as mental health treatment, peer support, and help with community reintegration. As a result:

“What would it mean if we saw the opportunity to recover as a right, and we had the political and moral imagination to confront all the ways that right is routinely denied to so many? To attempt to do so will pay great dividends, because especially in the case of addiction, what happens to one of us, affects all of us, and recovery is less an individual journey than a communal experience.”

Investing in Care Would Improve Our Economic Health for Decades to Come

Modern, evidence-based care has enormous potential to help Virginians who use opioids to stay alive. If we can help more people stay alive, we can also help them to reduce harmful use and live better – whether they continue active use or not. For people who are ready to stop using opioids, treatments that integrate medication for opioid use disorder can reduce fatal overdoses by 50%.27

Recovery would not only help people who use opioids to realize their potential – as parents, partners, friends, workers, students, volunteers, and the many other roles they may inhabit. Our data proves that better outcomes would also translate into enormous economic value. When we say that Virginians could collectively save $5.2 billion with more lives saved, we are referring to:

- the more than $2 billion in costs paid across all sectors in 2023 alone

- the billions more in productivity (lost labor) costs we expect to lose in the future, due to people losing their lives in 2023

Considering the economic costs actually paid in a single year, we could save more than $2 billion. If we include all the projected future workplace productivity costs – and tax revenue – also incurred in that same single year, we could save billions more in the decades to come. (For an exact breakdown of the data, view our methods.)

The need for strategic investment in a compassionate response is also more urgent than ever.

- The $1 billion that Virginia localities will receive from opioid settlement funds over 20 years represents only a tiny fraction of the costs our communities incur due to opioids in a single year.28 Payouts will also decrease over time.

- With public funding for Medicaid and other resources uncertain, we may not be able to sustain the apparent progress our communities have made in reducing overdose deaths.29

With less money available, investing it wisely is vital. We highlight research-backed response strategies that are not only cost-effective, but actually cost-saving – returning as much as 2100% on every dollar invested.30 Virginians deserve a healthier future – and now we have better data to plan out how we can afford to shape it.

Need help finding opioid care?

If you think someone is overdosing: Call 911 immediately. Learn about the signs of overdose. Virginia law provides anyone who calls 911 or otherwise alerts the authorities in the case of an overdose a "safe harbor" affirmative defense.

If someone you know needs help staying safe in active use and connecting to care: Find harm reduction services near you on VDH’s comprehensive harm reduction (CHR) center map.

If you are looking for evidence-based opioid care options for yourself or someone you care about: Explore your local options through Virginia’s publicly-funded, localized Community Services Boards.